Just over half a century ago the English heraldic world was rent by a controversy as to whether arms which were not on record in the College of Arms could lawfully be borne. The principal protagonists were A. C. Fox-Davies, who contended for the negative, and Oswald Barron, who took the diametrically opposite view.

The supporters of what may be called the Fox-Davies school of thought were unfortunate in their champion, for he concurrently advocated a theory that a grant of arms conferred a species of minor nobility and that no non-armigerous person could be a gentleman, which has tended to discredit his and his supporters’ views on arms in general. Furthermore it cannot be denied that Barron was a much more competent antiquary than Fox-Davies which no doubt explains why, in 1953, we still find people, and even responsible people, stating the extreme “Barronial” view that the arms which a man devises and assumes for himself are in every respect as valid as these granted by the Kings-of-Arms.

The matter in issue is a question of law. And that leads, or should lead, one to ask — what kind of law? Fox-Davies purported to be stating the Common Law, and relied upon a number of modern cases upon the construction of name and arms clauses. W. P. W. Phillimore, who was Fox-Davies principal supporter, drew analogies from the law relating to peerages, real property and even trade-marks. But this approach is fundamentally wrong. The Common Law had no concern with matters armorial.

The tribunal for heraldic cases was the Court of the Constable and the Marshal, known in post-medieval times as the Earl Marshal’s Court. It was often known as the Court of Chivalry, and as such it will be convenient to refer to it here. What was peculiar about it was that the law which it administered was not the English Common Law. This peculiarity the Court of Chivalry shared in this country with the Court of Admiralty and the Ecclesiastical Courts. These courts were entirely distinct from the ordinary Common Law courts, such as the King’s Bench, Common Pleas and Exchequer, and provided employment for a special race of lawyers — advocates and proctors, who professed the Civil Law(1) and the Canon Law.

The contention that a man may take such arms as he pleases without any grant, subject only to the proviso that they have not been borne by anyone else before, is founded upon a passage in the De Studio Militari of Nicholas Upton(2). Upton was an ecclesiastic and a graduate in both civil law and canon law. His work was based upon that of an eminent Italian civilian, Bartolus of Sasso-Ferranto, who is reputed to be the earliest writer on heraldry. In his turn Upton was copied by the author of the Book of St. Albans. Might it not then be said that Upton is a sound authority? Such an argument could only be based upon an imperfect understanding of the nature of the law administered in the Court of Chivalry.

Although the outlook of the civil lawyers in the Court of Chivalry was much more international than that of their Common Law brethren, the law which they administered was not foreign law, but a part of the law of England and was recognised as such by the Common Law courts. Thus in 1408 in the case of Grey v. Hastings in the Court of Chivalry we find a witness deposing that he had heard ancient men at arms and heralds of arms discussing the parties’ rights and concluding that the defendant had the better right ” according to the law of arms as used in England.”(3) Sir Edward Coke, writing two centuries later, confirms this, stating that the Court of Chivalry proceeds ” according to the customs and usages of that Court and, in cases omitted, according to the Civil Law, secundum legem Armorum.”(4).

The law administered in the Court of Chivalry was therefore a branch of English law, and recourse was only had to the Civil Law when the answer was not to be found in the customs and usages of the Court. To know the law of arms in England we must seek the customs and usages of the Court of Chivalry as interpreted by the civil lawyers. In addition to the proceedings of the Court, we may seek evidence of its customs and usages in the practice of the heralds, for in the absence of evidence to the contrary we are entitled to rely on the old legal maxim omnia praesumuntur rite esse acta, and so assume that the heralds were acting in accordance with law, at any rate during the period when the Court of Chivalry was active and could control their actions. It is only if these two sources fail us that we should look to the writings of jurists, and even then we should use those writings with extreme caution, particularly if the authors were foreigners or using foreign sources.

When the Court of Chivalry first obtained jurisdiction over armorial bearings is not at present known. It may be that when heraldry was first introduced men took what arms they pleased. Indeed we know that some continental writers likened arms to names, to be assumed and changed at pleasure and this seems to have continued in many European countries. Nevertheless by the first half of the fourteenth century we find the Court of Chivalry exercising jurisdiction in heraldic cases in England.

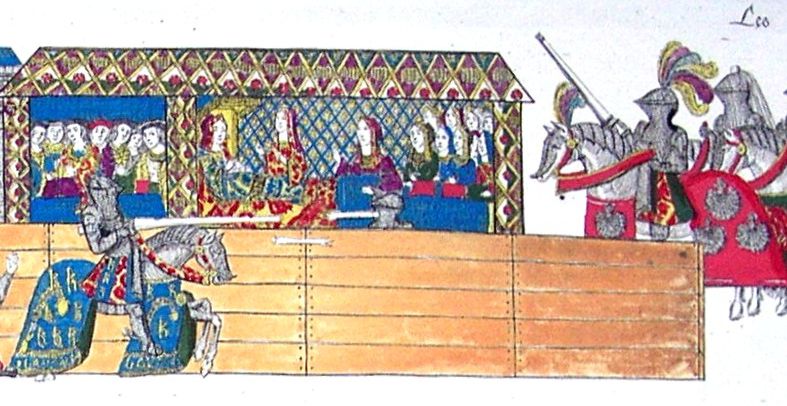

One of the few causes of arms in the Court of Chivalry of which we have a detailed record is the famous case of Scrope v. Grosvenor, which dragged on from 1385 to 1390. Unfortunately there is no reasoned judgement stating why the Court found in favour of the plaintiff. We have therefore to deduce what we can from the evidence (5). Both parties called numerous witnesses to prove that they and their ancestors had used the disputed arms over a long period. Some have seen in this merely a contest as to whose ancestor had first assumed the golden bend on the azure field of his own motion, and rely upon the case as authority for the Barron point of view. The form in which the evidence is given makes it clear that the case is not an authority for this point of view. Many of the witnesses stated that the arms had been borne by the ancestors of the party on whose behalf they were giving evidence from beyond the time of memory. This shows that an attempt was being made to prove user from time immemorial, which would give a good title under the Civil Law, as under the Common Law. Under the Common Law time immemorial was deemed to date from the accession of Richard I in 1189, and it is possible that the same rule applied in the Court of Chivalry, though the wording of the depositions in Scrope v. Grosvenor seems to indicate that the Norman Conquest was regarded as the limit of legal memory.

This is borne out by the case of Carminow v. Scrope, the only reliable account of which is to be found in the depositions of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster and other witnesses in Scrope v. Grosvenor. According to these witnesses it was proved that Carminow’s ancestors had borne Azure, a bend or since the time of King Arthur, and that Scrope’s ancestors had borne the same coat since the time of William the Conqueror. On this evidence it was adjudged that both might bear the arms entire. This decision is only explicable on the basis that both parties were entitled to the coat by virtue of user from time immemorial. Had the right depended on prior assumption, Carminow would have been solely entitled to the exclusion of Scrope.

Confirmation of the view that self-assumed arms were not regarded as lawful is to be found in a writ directed by Henry V to the Sheriffs of Hampshire, Wiltshire, Sussex and Dorset on 2 nd June, 1417. By this writ the Sheriffs were ordered to proclaim that no one should bear a coat of arms on the forthcoming expedition unless he possessed or ought to possess it in right of his ancestors, or by the grant of someone having sufficient power to make it, and that such a one should show by whose grant he holds his arms, those who had borne arms with the King at the battle of Agincourt only excepted (6).

Both the Barron and the Fox-Davies schools of thought read into this a statement that previously men had assumed arms of their own motion, and construe the writ as preserving that right to those who fought at Agincourt. Since the object of the writ was to regulate the army on a particular expedition, it seems more consistent with that object to regard the exemption of those who had fought at Agincourt not as conferring a sort of ” battle honour,” upon all who had fought there, but as showing that they had on that occasion proved their right to their arms, and relieving those of them proceeding on the later expedition from the necessity of repeating the proof.

We find the heralds acting upon the principle which we have deduced from Carminow v. Scrope and Scrope v. Grosvenor in confirming arms. Thus in 1454 Clarenceux King-of-Arms confirmed to John Aleyn the arms which ” his progenitours out of mind have borne “(7). In 1456 Guyan King-of-Arms confirmed arms which John Bangor and his progenitors ” time out of mind hath borne,” (8) and in 1470 Norroy King-of-Arms certified to the Prior of Bridlington certain arms, ” which armes of their family were for there ancestors by what right they were due to them for ever neither can tongue expresse or the memory of man recollect “(9).

Actual proof of user from so remote a time as before 1189 must have presented extreme difficulty, whilst proof of user before 1066 was, of course, impossible, and the nature of the evidence of user adduced in Scrope v. Grosvenor shows that the Court of Chivalry was prepared to hold that evidence of user during the time of living memory raised a presumption that the user had continued for the necessary period. This is reflected in the wording of confirmations of arms, which after the XVth century cease to refer to ” time out of mind ” and use vaguer expressions, such as ” ancient.” This modification of the wording of confirmations did not, however, reflect any change in the law, and even as late as 1633 Garter Burroughs confirmed a coat as having been borne ” tyme out of minde “.(10)

The extent of the antiquity of user in fact required is shown by a letter written by Sir William Dugdale, Garter King-of-Arms on 15th June, 1668, in which he states:—

” As for Mr. Raynes, if I can find anything in our books at the office to justifye the arms you drew with his descent, I will do it; but I have already perused some books and can find nothing out; therefore it will be requisite that he do look over his own evidences for some seals of arms, for perhaps it appears in them; and if so and that they have used it from the beginning of Queen Elizabeth’s reigne, or about that time, I shall then allowe thereof, for our directions are limiting us so to do, and not a shorter prescription of usage(11).

A few weeks before this letter was written the Commissioners for executing the Office of Earl Marshal had been authorised by Letters Patent dated 26th May, 1668 to make Rules to be observed by the Officers of Arms. The ” directions ” referred to by Dugdale were no doubt the Rules then in course of preparation. When the Rules were finally made on the following 22nd November they did not mention the beginning of the reign of Elizabeth I, but required that all certificates and other attestations of arms made by the Officer of Arms should contain ” a certain and particular reference to some Books in the Office of Arms ancient Deeds Records Monuments or other authentic Memorials of Antiquity justifying the same “(12). It would therefore appear that the law still required user from time immemorial to found a right to arms, but that this could be presumed on proof of user dating back before the reign of Elizabeth I, i.e., beyond the actual period of living memory.

The standard of proof required for certificates and other attestations of arms made by the Officers of Arms was slightly relaxed as respects visitations, the rule relating to the entering of arms at visitations being as follows: ” …..and that in all Cases

wherein the Arms claimed by any person or persons shall not be registred or entered in the Office of Arms or allowed by some former King of Arms or where a lawful Grant of the same made by a King of Arms shall not be exhibited or shall not be made out and proved either by some ancient Monument Glass Windows Impressions of Seals or other credible Testimony that the same Arms have been born and used by the Ancestors of the Party claiming them for the space of sixty years at the least before the time of that his claim; such Arms shall not be allowed or entered “(13).

This acceptance of sixty years’ user for the purposes of future visitations did not however, affect the requirement of proof dating back to a more remote period in all other cases. Barron and his followers drew a very different deduction from Dugdale’s statement. Apparently unmindful of any inconsistency with their other contention that a man could assume arms of his own motion and thereupon acquire a right to them, they argued that because a period of 100 years had elapsed between the beginning of the reign of Elizabeth I and the date of Dugdale’s letter, the use of arms for a period of 100 years gave a prescriptive right to them, so that in the year 1953 it would only be necessary to prove user since 1853(14). This argument is based on a misunderstanding of the history of the law of prescription. Originally user for a long period did not of itself confer any right either under the Civil Law administered in the Court of Chivalry, or the Common Law — it was only evidence from which user from time immemorial, which alone gave rise to a right, could be inferred. It was not until the Prescription Act, 1832 that the form of prescription which Barron had in mind was introduced. Under that Act the enjoyment of certain easements for specified periods gave a right to those easements, but the Act had no application to arms.

User to support a claim by prescription must be such as will justify an inference that the user commenced before the time of legal memory. To prove such a user today would be a matter of considerable difficulty. During the century and a half between 1530 and 1687 every county in England was visited by the heralds, some of them on more than one occasion, so that every armigerous person had the opportunity of entering his arms. Any coat which has been in use from time immemorial must ex hypothesi have been in use during that period, and the fact that a coat now alleged to have been in use from time immemorial does not appear in any visitation record must

raise a prima facie presumption that the coat was not in use during that period.

Doubtless there are persons now living whose ancestors were entitled to arms and failed to obey the heralds’ summons, but the onus of proving their right would be a heavy one. Evidence of a mere private user, e.g. on family plate, would not be enough. It would have to be shown that the arms had been borne coram publico, e.g. on tombstones, for it is an old and well-established rule, both in the Civil Law and the Common Law, that no reliance can be placed on clandestine user to support a claim to an incorporeal right. The evidence would have to be that the arms had been borne (to use the words of some of the witnesses in Scrope v. Grosvenor) ” publikement, pesiblement & quietment.”(15)

Thus we can find nothing in the customs and usages of the Court of Chivalry or in the practice of the heralds, which may be taken as reflecting those customs and usages, to support Nicholas Upton’s dictum. On the contrary, far from a man being able to assume arms at pleasure, his arms must be evidenced either by an actual grant or by user of such a length and such a nature as will give rise to a presumption that the arms have been used from time immemorial.

It seems to be a sound working rule for the present day to refuse to acknowledge arms which cannot be shown to have been either granted or entered at a Visitation.

REFERENCES

(1) The expression ” civil law ” is here used not in contra-distinction to criminal law, but as meaning the Roman law of the Corpus Juris Civilis, compiled by the Emperor Justinian in the sixth century, A.D.

(2) ” Meny by ther owne auctoritie take armys upone them and to ther heyres. Never thelesse soche arms may frely and lawefully be borne, yff they be not borne by someother.” Nicholas Upton’s De Studio Militari.. Translated by John Blount..(c. 1500) (1931). P.48.

(3) A. R. Wagner, Heralds and Heraldry in the Middle Ages (1939), p.24

(4) Fourth Institute, p. 125.

(5) Printed in N. H. Nicolas, The Scrope and Grosvenor Controversy (1832),

Vol. la

(6) The text of this writ is printed in “X” (i.e., A. C. Fox-Davies) The Right to Bear Arms (1900), p.44-45.

(7) Miscellaneous Grants (Harl. Soc. Vol. lxxvi) (1925), p.2.

(8) Misc. Gen. et Her. I, p.54.

(9) Heraldic Visitation of the Northern Counties in 1530 (Surtees Soc, Vol. xli) App., p.xxxviii.

(10) See a collection of extracts from confirmations in The Ancestor (1904), VIII, pp. 124-141.

(11) The Ancestor (1902), II, p.45.

(12) Printed in Minutes of Evidence in Roos Peerage Case (1804), p.335.

(13) Ibid., p.333.

(14) See “The Prescriptive Usage of Arms,” The Ancestor (1902) II, p.45. W. Paley Baildon, ” Heralds’ College and Prescription,” The Ancestor (1904) VIII, p.144 stated that ” a reasonable length of user ” was all that was required.

(15) Scrope and Grosvenor Controversy, I. pp.296-297.