The Cloth-Armourers used leather, gesso, brocades and embroideries

The Cloth-Armourers used leather, gesso, brocades and embroideries

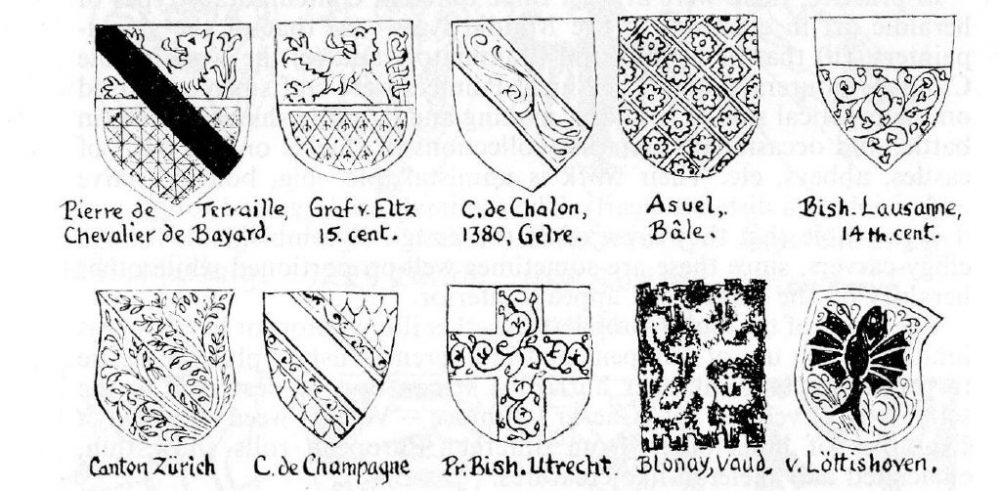

The art of heraldry is a law unto itself: its standards and forms differed in every age, in each country and varying materials. The use of different media has modified the artistic representation; the shield-painters (and originally the tomb-carvers) produced plain broad shields. Clothiers and embroiderers made surcoats, horse-trappers, banners, etc. with a wealth of patterned cloth to break up the surfaces, which was copied later by the glass-stainers. It was the use of these patterned materials which produced the much-misunderstood ‘diapered’ — it crept into heraldry ‘by the back-door’ due to ignorance on the part of the paper-heraldists.

In the Middle Ages the work of the herald artist was divided between (a) that of the shield-painters, (b) that of heralds and illuminators and (c) the work of the Cloth-Armourers’ Guild. The Shield-Painters were craftsmen employed on the practical side of heraldry, making and painting shields for use in battle, and occasionally painting collections of shields on the walls of castles, abbeys, etc. Their work is unmistakable — big, bold, effective and visible at a distance clearly.

The glory of pomp and luxury was in essence the output of the Cloth-Armourers, whose guild was entirely separate from the Helm-Makers who produced breastplates, body-armour and helmets. Nearly sixty percent of the battle-armour and ninety percent of parade-armour was fabricated by the Cloth-Armourers from boiled leather, thick canvas or padded linen lined with metal plates, or studded with metal bosses like large sequins. For battle this type of protection was painted, gilded or covered in coloured cloth: for tourneys and pageants the covering was velvet, silk or one of the wonderful patterned textiles imported from the Byzantine Empire or the East, with shade-variations of design or woven with motifs in gold or silver threads.

These textiles bear today the Eastern names given to them by the mediaeval merchants at the great continental fairs — damask (from Damascus), muslin (Mosul), diaper (from the Byzantine διβαφος dibaphos, the rich gold embroidered material used for making the robes of court officials and the copes of the Orthodox Church).*

ClothArmourers made the great, ornate saddles of wood and the pageantshields, which were either modelled in leather or gesso, or covered in coloured brocades and clothofgold or ofsilver. These fine ‘works of art’ were often copied onto painted rolls as ‘diaper’ but had no heraldic significance: it merely indicated that the compiler had used a pageantand not a battleshield when emblasoning his paper heraldry.

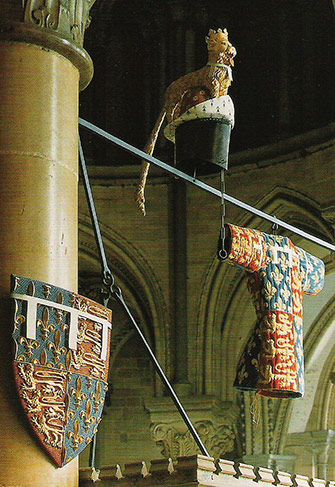

Examples of Cloth-Armourers’ work are the shield of the Black Prince at Canterbury and the Cluny horse-trapper with its background of delicate gold foliage.

The restored Black Prince's tabard, shield and helmet above his tomb at Canterbury Cathedral

The restored Black Prince's tabard, shield and helmet above his tomb at Canterbury Cathedral

The development of pageant heraldry can easily be discerned in the work of the glass-stainer. The early thirteenth century windows in Chartres Cathedral show heraldry in rich, deep, plain colours; the work of Swiss masters like Zeiner, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, invariably consists of patterned glass to represent diaper cloth.

Apart from the early incised slabs, the stone-carvers — whose daily work was on tombs (cathedrals and abbeys were only occasional) — tended to follow the embossed reliefs of elaborate modelled pageant shields since this gave the best effect in stone. The Percy tomb at Beverley is a fine example, which discloses its origin not only in high relief but in the diapering of plain surfaces.

When battle heraldry became obsolete in the fifteenth century, both shield-painting and serious roll-emblasoning went out of use. This left pageant heraldry to carry on alone, and a highly elaborate and artificial style was developed at the court of Burgundy, which spread over Renaissance Europe, giving us the typical elegant and decorative lions which would have appeared effeminate to the shield painters of the Gothic Age.