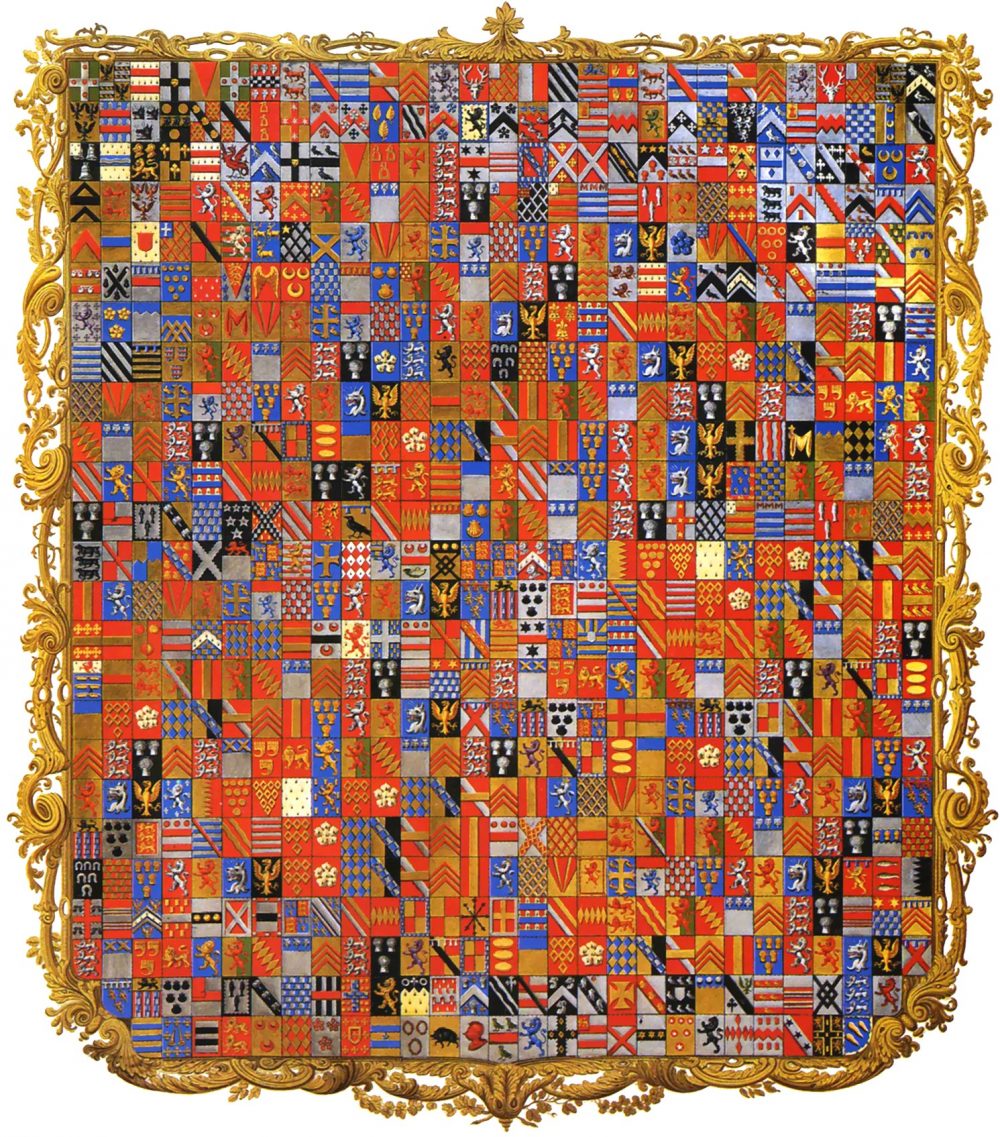

An extreme example of multiple quarterings, with heiresses having many ancestors in common

An extreme example of multiple quarterings, with heiresses having many ancestors in common

In the marital achievement of a man and an heiress, her arms are displayed on his, in an escutcheon of pretence. A man who marries an armigerous woman, not an heiress, impales her arms.

A spinster bears her father’s arms in a lozenge with no crest or other trappings. A married woman bears her married arms in a shield but still without trappings. In widowhood a woman continues to bear the married escutcheon but on a lozenge. A married woman seldom bears arms apart from her husband though since the passing of the Married Women’s Property Act one can conceive cases where she might wish to display arms suo jure.

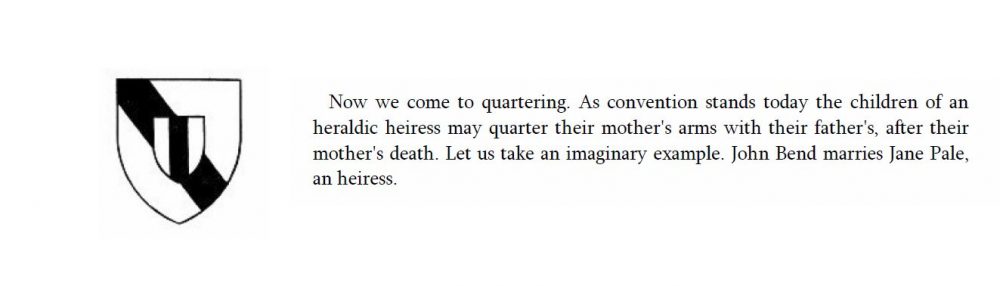

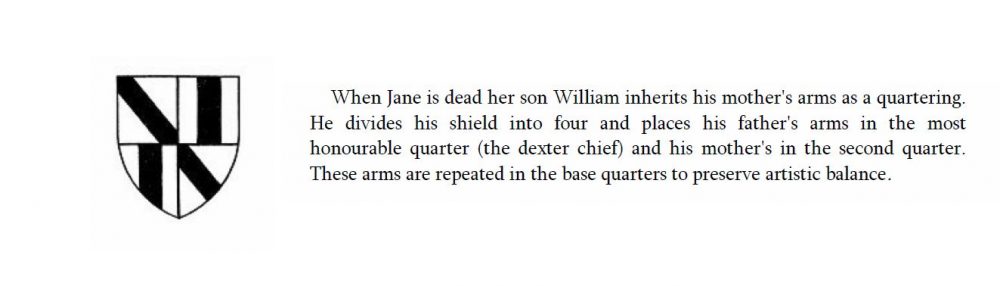

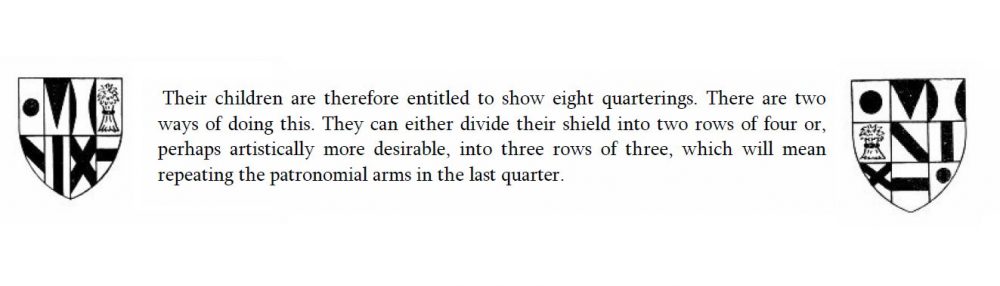

It will be noticed that the word quartering is an euphemism and means the division of the shield into any number of parts, not merely the four implicit in the meaning of the word.

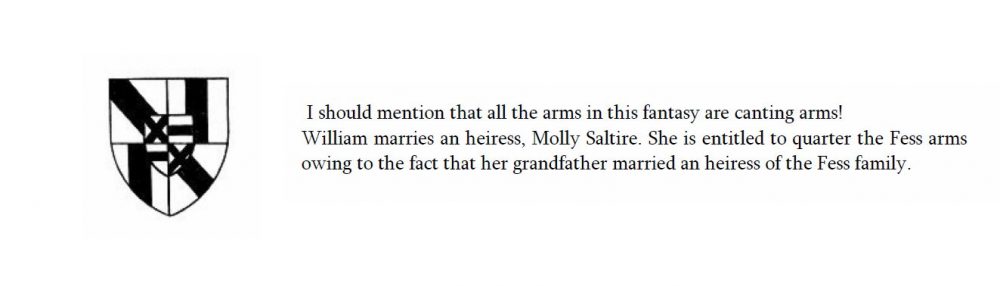

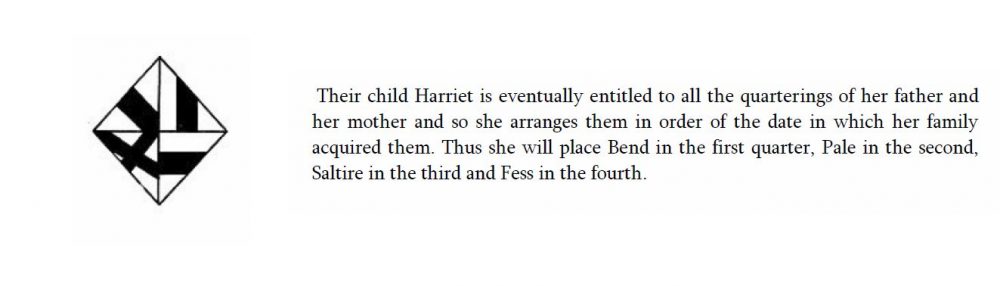

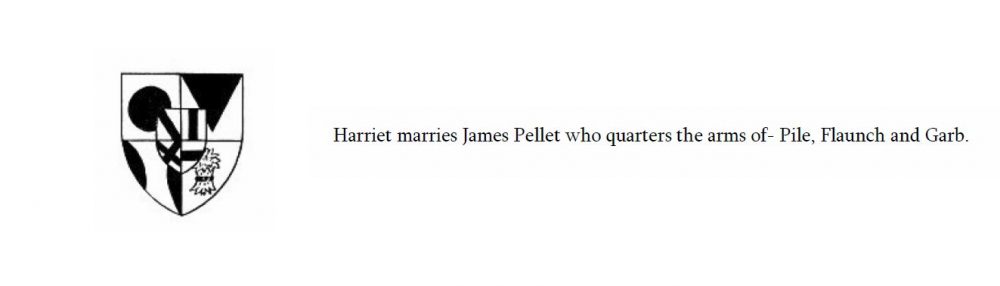

In theory the sky is the limit when quartering. There are two points worth remembering with regard to quartering. The first is that quarterings can only be acquired through an armigerous person. Your mother may have been the Duke of Ballynahinch’s only child but unless you are armigerous you cannot inherit her noble quarterings. The second point is that the dexter chief is reserved for the patronomial arms, and is the first quartering; the quarterings being numbered across — two, three, four, etc. and you read them just like a book, the quarterings nearest to the patronomial arms having been acquired first. If you have to repeat one or two quarterings to balance the shield you put the first in the last, the second in the penultimate and so on. It is not often that it is necessary to repeat more than the first two. When blazoning a quartered shield you say; quarterly, 1. so and so, 2. such and such, etc. If the shield is quarterly of more than the usual four you say; quarterly of eight (or however many it may be) and then as before, numbering each quartering before blazoning it.

It is of course impossible to exhibit more than a very few quarterings in the everyday display of arms, but it is of great historical and heraldic interest to have a record of all the quarterings to which you are entitled. I would suggest that the full achievement of your family should have a place in the house, be it never so unostentatious. For the ordinary display of arms the use of one coat is usually most artistic and convenient. On seals and stationery a quartered coat does not often come out well. The charges have to be engraved so minutely that they lose their form and the ancient purpose of armorial bearings is lost. Even on china four quarterings will be found to be ample. It is, I think, and this is only a personal opinion, best to use one coat only unless you have a compound surname, all the names in which indicate heirship; or unless you are the senior heir of a famous family, or if you have inherited lands or titles from some family whose arms you are entitled to quarter.

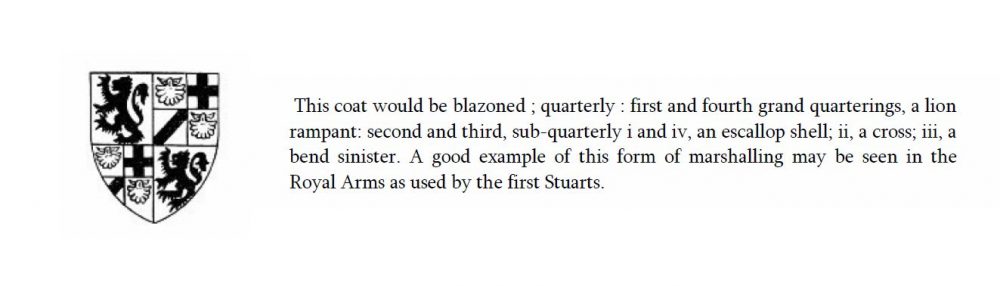

In Scotland they go about the business of quartering in a slightly different way. I shall not here discuss the rules employed but would like to illustrate one major difference, that it may be recognised when seen. When a man inherits quarterings from his mother he may divide his shield into four ” grand quarterings ” placing his father’s entire coat in the first and fourth and his mother’s in the second and third.